Boston Premiere!

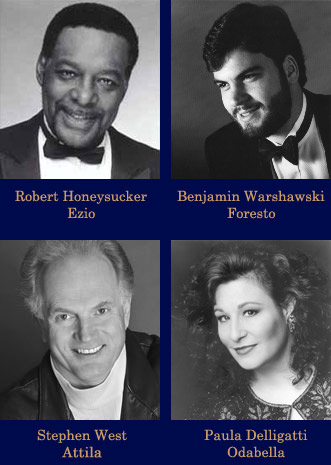

On Sunday, June 4, 2006, Concert Opera Boston sponsored a concert performance of Verdi’s Attila at the New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall at 3pm. This was the Boston premiere! Peter Grahaeme Woolf in Seen and Heard International writes of Attila: “A youthful, rousing barnstormer of a piece, Attila races through a plot that cheerfully rewrites history to terrific musical effect. There are hints of the dramatic richness which was about to flower in Verdi’s next work, Macbeth, but what is really remarkable about this opera is its irresistible energy. The action is tied together by thundering orchestral writing, massive patriotic crowd scenes, and a gutsy sense of good versus evil. The last of these is personified by Attila himself, the rampaging barbarian who nevertheless achieves surprising nobility.” The role of Attila was sung by bass Stephen West, who sung it to acclaim at the New York City Opera. Paula Delligatti, who sang Madama Butterfly with the Boston Symphony several seasons ago, sang Odabella. Boston favorite Robert Honeysucker and tenor Benjamin Warshawski completed the stellar cast. They were joined by Chorus pro Musica and an orchestra of outstanding Boston musicians all under the baton of Jeffrey Rink.

And the press wrote:

"Verdi's 'Attila' is a brawling, lusty opera that got just that kind of performance from music director Jeffrey Rink, Chorus pro Musica, and an uninhibited cast on Sunday…Veteran Boston baritone Robert Honeysucker took the part of the stalwart Roman general Ezio… His presence and singing had weight and force, and his voice rolled magnificently through the music…Paula Delligatti…commands the style and cannily substitutes accent for power, maneuvering through the music's hairpin turns more smoothly than most dramatic sopranos, and without squealing brakes. She also knows how to stand there and flash her eyes like a weapon…Tenor Benjamin Warschawski sang her beloved, Foresto, with attractive tone and line…In the title role, bass Stephen West had the right melodramatic instincts and repeatedly went for broke…This was the 11th opera presented by Rink and Chorus pro Musica (10 of them substantially underwritten by Concert Opera Boston)…The Chorus pro Musica offered ringing tone and disciplined enthusiasm. The orchestra, full of veterans of Boston's opera wars, played a fiery performance for Rink, who commands all the skills of operatic conducting. Like a conqueror he knows where he wants to go and how to inspire his troops to get there." - Richard Dyer, Boston Globe, June 7, 2006

"I’ve been more than impressed with the way Rink handles opera — and especially Verdi…The Chorus itself shone as both ravenous Germanic cannibals and fervent hermits…and that was especially important because Verdi structures this opera around contrasting choruses. Rink’s superb orchestra played not only with unflagging energy but also with finesse. He shaped those musical arches and made every change in tempo tell. There wasn’t a dull second. In a cast of singers with the classiest credentials — Metropolitan Opera, New York City Opera, Covent Garden, Bayreuth…Boston’s own Robert Honeysucker[’s]…suave and ringing baritone just gets more beautiful and powerful…In the title role, bass-baritone Stephen West gave the fullest characterization to the most fully characterized part in the opera…West has a strong, rough voice that’s perfectly appropriate here. And he caught the dramatic nuances…Delligatti has technique, pitch, and a pretty voice… City Opera tenor Benjamin Warshawski… projected well over the orchestra…They all contributed to the delight of the nearly sold-out crowd at Jordan Hall. Rink’s concert operas have caught on." - Lloyd Schwartz, Boston Phoenix, June 7, 2006

Stephen West: In a distinguished career spanning over three decades, bass-baritone Stephen West has appeared with many of the finest opera companies in the world, including the Metropolitan Opera, the Bayreuth, Salzburg and Santa Fe Festivals, the Opéra National de Paris, Deutsche Staatsoper, Teatro Carlo Felice and Teatro Regio, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, New York City Opera and the San Francisco, Seattle, Washington and Dallas Operas, among many others. He is a frequent guest with symphony orchestras such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Boston, Atlanta, Montreal and Columbus Symphonies, and the Philadelphia and Cleveland Orchestras in venues such as the Hollywood Bowl, Tanglewood and Carnegie Hall. He has appeared with many of the most famous conductors in the world including James Levine, Riccardo Muti, Sir Andrew Davis, Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, Christoph von Dohnányi, Alessandro Siciliani, Antonio Pappano, Sir Charles Mackerras, Julius Rudel, Michael Gielen, and Richard Bonynge. continued

Paula Delligatti: Since her European debut in 1997, soprano Paula Delligatti is a regular guest of leading opera houses and symphonies throughout Europe and the United States. She has appeared with the Opera National de Paris-Bastille, Teatro Comunale Firenze, Deutsche Staatsoper and Deutsche Oper (Berlin), Pittsburgh Opera, Houston Grand Opera, New York City Opera, and Opera Pacific as Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (London) and the Teatro Comunale di Bologna as Amalia in I Masnadieri and the title role in Bellini's Norma in Sicily. continued

Robert Honeysucker: Baritone ROBERT HONEYSUCKER is recognized internationally for his brilliant opera, concert and recital performances. His voice has inspired critical acclaim: "...powerful, passionate and plaintive....a voice that possesses great richness and warmth." Honored as 1995 “Musician of the Year" by The Boston Globe critic Richard Dyer, Mr. Honeysucker has also been a winner of the National Opera Association Artists Competition and a recipient of the New England Opera Club Jacopo Peri Award. continued

Benjamin Warshawski: Career highlights have included Alfredo in La Traviata with New York City Opera, OperaDelaware, and Bohème Opera New Jersey; Edgardo in Lucia Di Lammermoor with Sarasota Opera and Nashville Opera; the Duke in Rigoletto with Opera Illinois, Austin Lyric Opera, Augusta Opera, and Annapolis Opera; Cavaradossi in Tosca with Augusta Opera; the title roles in Werther and in Puccini’s Edgar with Dicapo Opera Theatre; Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly with Augusta Opera and Capitol City Opera; and Don José in Carmen with Tri-Cities Opera. Concert highlights have included Rodolfo in La Bohème and Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly with the Newton Symphony Orchestra; a command performance of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta at the Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C.; David Israel’s El Yerushalayim with the American Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leon Botstein at Alice Tully Hall; Berlioz’s L’Enfance Du Christ and Handel’s Messiah with the National Chamber Orchestra; Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with the North Arkansas Symphony and the Fairfax Symphony; Opera Galas with the North Arkansas Symphony, the Gold Coast Symphony, and the Richard Tucker Foundation; Cantorial Concerts in New York, Miami, Montreal, and Toronto; recitals in Baltimore, Atlanta, Strasbourg, Zürich, and Basel (Switzerland); and a Holiday Concert at the White House for President and Mrs. Clinton. His discography includes three CDs with XLNC Records.

Notes on “Attila”

Attila, Verdi’s ninth opera, was written in the aftermath of his biggest operatic failure since the fiasco of Un giorno di regno in 1840: Alzira, which had its premiere in Naples in 1845. In addition, Verdi was suffering from a number of physical ailments that caused him to be bedridden for nearly two months in early 1846. Despite his physical condition, and the severe depression that followed, Verdi gave in to pressure from the music publisher Francesco Lucca and consented to compose an opera for Venice’s La Fenice. Verdi may have been motivated to write an opera for Lucca partly to spite his former publisher, Ricordi, who until that time had an exclusive arrangement to publish all of Verdi’s operas, and with whom Verdi was now feuding; but perhaps more significantly, Lucca agreed to handle all negotiations with the management of the theater. Although thus freed from the usual responsibilities of casting and staging the work and negotiating with the censors, Verdi still described his state on completing the composition as "an almost dying condition."

While searching for a suitable subject for this opera, which he knew had to be a success to erase the memories of Alzira, Verdi had read the play Attila, König der Hunnen (1808) by the German playwright and poet Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner (1768–1823), in Italian translation as Attila re degli Unni. The play had been considered for operatic treatment by Beethoven, and it had also been the source of an opera by Malipirso, Ildegonda di Borgogna, which was performed in Venice the same year that Verdi’s opera premiered. It contains many elements that separate it from the kinds of Italian sources Verdi had previously used (although the play may have been inspired by an Italian opera, Attila, by Farinelli, composed in 1807): It draws on three Norse sagas, the Poetic Edda, the Niebelungenlied, and the Volsung Saga, the latter two of which served as sources for Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen; in the Nibelungenlied, Attila appears as King Etzel of Hungary; in the Poetic Edda and the Volsung Saga he appears as Atli; in these sources, he marries Kriemhild (Gudrun, Wagner’s Gutrune) after the death of Siegfried.

The Huns, apparently an extension of the Xiongnu of northeastern China, were highly sophisticated soldiers who added to their ranks as they conquered; at their peak they numbered as many as 700,000 soldiers. Originally horse soldiers, they were forced by local conditions as they moved west to develop an infantry. Attila (406–453) reigned as their king from 433 to 453; until 445 he shared the throne with his brother Bleda, but he killed him in 445. As a result of the devastation Attila and his Huns wreaked on Asia and Europe, Attila became known as the “Scourge of God,” and rumors that he practiced cannibalism only added to his mystique. Under Attila, the Huns conquered Persia, then the entire region between the Black and Caspian Seas, then Gaul, and finally the Roman Empire. After destroying the city of Aquileia, the Huns ravaged the Italian cities of Treviso, Padua, Verona, Cremona, Bergamo, Milan, and Ferrara, among others. According to legend, Attila claimed that he had received a large portion of the Roman Empire as a dowry and asserted that in taking the western part of the Roman Empire he was merely claiming by force what was rightfully his. Mystery surrounds the reasons for Attila’s retreat from Rome after a meeting with Pope Leo I, which is depicted in a painting by Raphael. Legend has it that he was frightened by a vision of a threatening figure hovering in the air, but it is more likely that plague and famine were at least partly responsible for the Huns leaving Rome. Although the Norse sagas relate that Attila dies by the hand of one of his wives (usually Ildico [Hildegonde]), Attila choked to death as a result of a nosebleed, according to the Greek historian Priscus, or possibly from overindulgence at a feast.

At first glance, it is hard to understand what attracted Verdi to Werner’s play, given the unsavory reputation of its title character and its heavily Germanic romanticism, with its references to the Norns, Valhalla, Wotan’s sword, and the pantheon of Norse gods and goddesses. But Verdi was impressed by the play’s themes of devotion, patriotism, betrayal, and vengeance, along with its elements of Christian mysticism. He was also attracted by the drama of Attila’s decision not to destroy Rome. In a letter to the librettist Francesco Maria Piave, Verdi commented on the play’s operatic use of choruses, which he called “magnificent.” Above all, Verdi was attracted by the play’s strong characters—“tre caratteri stupendi,” as he called them—none of whom he saw simplistically as heroes or villains. In Attila, despite his obvious ruthlessness, Verdi found a man of loyalty and honesty.

In the play, Attila has been chosen by Wotan to encourage bravery among his people and to punish cowardice. Attila had killed in battle the family of the princess Hildegonde as well as her fiancé, Walther; to take revenge on Attila, she pretends to be a devoted follower with the goal of marrying him and then killing him on their wedding night. Determined to kill Attila, she prevents a Roman soldier from poisoning him so that she can perform the deed herself. As Attila’s blood brother, the Roman general Aetius is distrusted by his fellow Romans, but the Romans are depending on him to lead them to victory against the Huns. Leo, here described as a bishop rather than the pope, represents Christianity and voices the theme of redemption through love; he also helps Attila reconcile death with the promise of eternal life in the hereafter. Once Hildegonde has stabbed Attila and his son, she attempts to take her own life but is then killed by one of Attila’s soldiers.

Verdi’s chosen librettist, Temistocle Solera, had already contributed several librettos to Verdi: Oberto, Nabucco, I Lombardi, and Giovanna d’Arco. The relationship this time, however, was not ideal. Solera betrayed signs of disinterest and, after procrastinating in finishing the libretto, eventually left with his wife for Madrid, having given Verdi permission to have Francesco Maria Piave, the librettist of Ernani, complete Attila’s libretto. Verdi’s continuing ill health and his dissatisfaction with Piave’s work led him to send Solera Piave’s libretto for the last act; Solera became incensed when he realized that his idea for a choral finale had been ignored—on Verdi’s orders. The resulting rift ended any future collaboration with Verdi and led to Solera’s retirement as a librettist.

The final version of the libretto reorders and simplifies the play, eliminating and conflating some of Werner’s characters. Hildegonde becomes Odabella; Aetius becomes Ezio, who is not killed in battle but survives to the end of the opera; Walther, Hildegonde’s betrothed, has not been killed by Attila and becomes Foresto, who is based on a historical figure. Under pressure from the censors, who prohibited the theatrical portrayal of a pope, Solera further diminishes Leo, who becomes simply “an ancient Roman.” Ezio, who is killed off earlier in the play, is allowed to survive to participate in the final scene of the opera. The slave Uldino is not found in the play.

Although the opera is firmly in the style of Verdi’s Risorgimento operas, with its unison choruses and noisy marches, along with a continuing dependence on the established operatic structure of recitative, cavatina, and cabaletta, it exhibits a more imaginative use of the orchestra than Verdi had shown previously, as well as a greater consistency of style than the operas that preceded it. Although the music lacks the harmonic sophistication of Verdi’s later operas, it features a number of remarkable effects, including the orchestral representation of a sunrise in act one and the meltingly beautiful accompaniment by harp, cello, cor anglais, and flute to Odabella’s aria “Ah nel fulgente nuvolo” in Act One. It contains two notable arias for the tenor, a baritone aria, “Dagli immortali vertici,” featuring Verdi’s trademark soaring, archlike phrases, and the lyrical trio “Te sol, te sol quest’amima.”

For the three main characters, Verdi scored Attila for bass-baritone, Ezio for baritone, and Odabella for dramatic soprano, in the tradition of such difficult dramatic Verdi soprano roles as Abagaille in Nabucco and Lady Macbeth in Verdi’s next opera; it requires a wide-ranging voice capable of riding over the large orchestra but with substantial agility, as in her opening aria, “Allor che i forti corrono” (which features a high D-flat in its first bars) and its fearsome cabaletta, “A te questo or m’è concesso.” Foresto supplies the expected tenorial love interest for the soprano.

The premiere of Attila took place at the Teatro La Fenice, Venice, on 17 March 1846 and was well received, despite singers who were reportedly not in their best voice and some staging mishaps, including some foul-smelling candles used in the scene of Attila’s feast in Act Two. The critics were somewhat dismissive, but the audience was enthusiastic. As Verdi’s pupil Emmanuele Muzio wrote to Antonio Barezzi on 23 March 1846, “Attila has aroused real fanaticism; the Signor Maestro had every imaginable honor: wreaths, and a brass band with torches that accompanied him, to his lodging, amid cheering crowds.” Verdi himself wrote to his friend Countess Maffei that “Attila had, on the whole, a very cheerful reception. . . . My friends maintain that this is the best of my operas. . . . I think it is not inferior to the others. Time will tell.” The positive reaction by the Venetian audience was no doubt intensified by the second scene of the prelude, in which a vividly depicted sunrise following a raging storm inspires a chorus of fugitives from Aquileia to sing of the new city that will rise like a phoenix on these now barren shores of the Adriatic. Throughout Italy, audiences seeking independence from Austrian rule responded to the patriotism of Odabella’s aria in praise of the bravery of Italian women and, especially, to the resonance of Ezio’s line, “Avrai tu l’universo, resti l’Italia a me!” (“You take the universe, but leave me Italy”; one wonders how this line passed the Austrian censors. For the performances in Trieste in the fall of 1846, Verdi wrote an alternate aria, written for the tenor Ivanoff (the aria was never published and its score remains in private hands and unavailable). He wrote a second alternate aria for the tenor Moriani when the opera was revived at La Scala in the carnival season of 1846-1847. These first performances at La Scala were also well received by the public, but Verdi, whose relations with La Scala’s impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, had become strained, was reportedly highly dissatisfied with the way Attila had been produced, so much so that he announced that he would not let any more of his operas have their premieres there (he later relented, and the revised versions of Simon Boccanegra, La Forza del Destino, and Don Carlos, were first performed there, as were the premieres of Otello and Falstaff). Attila’s popularity spread rapidly, even outside Italy; it traveled to Madrid, Copenhagen, and Havana within three years; it was seen in England at Her Majesty’s Theatre, London, on 14 March 1848; and it arrived in the United States at Niblo’s Theater, New York, on 15 April 1850. It reached the Liceu in Barcelona in the 1850/51 season, where it received twenty performances before disappearing from the stage in 1856. Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro saw it in 1853. Then, suddenly, except for a few late-nineteenth-century revivals, it suffered a long period of neglect. Its resurrection came in 1951 when it was revived in Venice in a concert performance under Carlo Maria Giulini. Its next major revival occurred when it was staged in Florence in 1962, with Boris Christoff singing Attila and Bruno Bartoletti conducting. Since the 1970s it has begun to be performed with increasing frequency: It reappeared at the Liceu in the 1973/74 season, with a revival in 1983/84; La Scala revived it in its 1974/75 season; it received its Vienna Premiere in 1980; and the New York City Opera presented it in its 1981 and 1985 seasons. Elijah Moshinsky directed Covent Garden’s first performances in 1990. Attila was staged in Nice in 1993/94, but it was not seen at the Paris Opéra until 2001. Although it has been mounted at the Chicago Lyric Opera and other major American companies, it has never been performed by the Metropolitan Opera; the only music from Attila that has ever been performed at the Metropolitan Opera House is Attila’s aria “ Mentre gonfiarsi l'anima,” which was sung by Justino Díaz at the MET Marathon on September 26, 1975. The performance by Chorus pro Musica represented the first time the score has been heard in Boston.

The opera has received two commercial studio recordings; one with Ruggero Raimondi (Attila), Sherrill Milnes (Ezio), Christina Deutekom (Odabella), and Carlo Bergonzi (Foresto), under Lamberto Gardelli, and one with Samuel Ramey, Giorgio Zancanaro, Cheryl Studer, and Neil Shicoff, under Riccardo Muti. It is also available in several live recordings (including the Venice revival of 1951) and DVDs including an Arena di Verona performance with Nesterenko, Maria Chiara, and Veriano Luchetti under Nello Santi; and a La Scala performance with Ramey, Zancanaro, Studer, and Kaludi Kaludov under Riccardo Muti. Relatively few individual pieces from the opera have been recorded. The only portions of the opera that were recorded in the early years of recorded sound were the baritone aria “Dagli immortali vertici,” which received what was probably its first recording in 1921 by Mario Laurenti and was later given a classic reading by Igor Gorin, and the last-act trio, “Te sol, te sol quest'anima,” which received a famous recording in 1930 by Ezio Pinza, Elizabeth Rethberg, and Beniamino Gigli; in the first decade of the twentieth century, the trio was frequently recorded as a hymn, under the title “Praise Ye,” with new English words that bear no relation to the original Italian text. Odabella’s entrance aria has been recorded by Joan Sutherland and Beverly Sills (both with added ornamentation); her second aria, “Ah nel fulgente nuvolo,” is included in Montserrat Caballe’s Verdi, Donizetti, and Rossini Rarities CD and is also found in one of Maria Callas’s CDs of Verdi arias. Enzo’s aria has been recorded by Sherrill Milnes, among others. Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo, and Ramon Vargas have recorded the alternate aria for Foresto, “O Dolore . . . Fui beato in quell’amore,” written for the La Scala performances of 1846–1847. The Attila-Enzo duet “Uldino, a me dinanzi . . . Tardo per gli anni” is included in the CD “No Tenors Allowed,” with Samuel Ramey and Thomas Hampson. Attila’s “Uldino, Uldin” can be heard in a recording by Egils Silins with the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra under Alexander Vilumanis. The opening chorus “Urli, rapine” can be heard in a collection by the Accademia di Santa Cecilia.

--Michael Sims

Other information:

The mission of Concert Opera Boston is to sponsor outstanding and affordable performances of concert opera in the greater Boston area. Concert Opera Boston also supports educational activities and other initiatives that enhance the appreciation of opera