Concert Performance

Sunday, June 1, 2008 at 3PM

New England Conservatory's Jordan Hall, Boston

Bizet's Carmen

conducted by Jeffrey Rink

Concert Opera Boston was proud to be the major sponsor of Chorus pro Musica's sold out concert opera performance on June 1, 2008 of one of the world’s most popular operas, Carmen. Premiered at the Opéra Comique in Paris on March 3, 1875, it was initially considered a failure, denounced by critics as "immoral" and "superficial." Today it is the fourth most performed opera in North America. Carmen, a beautiful gypsy with a fiery temper, has had many lovers. She woos Don José, an army corporal, who falls in love with her and eventually is driven to madness when she leaves him for the bullfighter Escamillo. Several of the pieces from the opera have taken on a life separate from the work including the "Toréador Song" and the "Habañera." Maestro Jeffrey Rink was joined by a stellar cast that included Victoria Livengood as Carmen, Adam Klein as Don José, Robert Honeysuckerr as Escamillo, and Nouné Karapetian as Micaela. They were joined by Chorus pro Musica and orchestra. The performance was sung in French with translations projected in English. The pre-concert talk was given by Michael Sims, author of Concert Opera Boston’s notes on Carmen and previous operas.

The critics praised the performance:

“Jeffrey Rink has just ended his 18th and final season as music director of Chorus pro Musica…He’ll be missed — especially his series of accomplished concert operas, landmarks of Boston’s recent musical history. His swan song (though the program says he’ll be back to conduct next year’s CpM Turandot) was the opera he began with in 1992, Carmen, and his conducting was, once again, stylish, incisive, colorful (Julia Skolnik, flute, and Martha Moor, harp, in the atmospheric second entr’acte, for example), propulsive, witty, and — when called for — grandly tragic. The chorus, and the NEC Children’s Chorus, sang with verve — and good French. And the superb orchestra was on its game. Carmen needs a strong cast, and this performance had one. Tenor Adam Klein doesn’t have a meltingly beautiful voice, but his grim ferocity made Don José’s murder of Carmen inevitable. Young Armenian-American soprano Nouné Karapetian as Micaela had a distinctive timbre, a lovely presence... Veteran Boston baritone Robert Honeysucker sang the bullfighter Escamillo with eloquence and tonal radiance. His “Toreador Song” was the song of seduction Bizet intended. His was the most thoroughly satisfying performance — and not for the first time. John Gomez and Gregg Jacobson were lively smugglers, and Sarah Beckham and Sara Bielanski were appealing as Carmen’s Gypsy pals (the mercurial second-act quintet was a high point)…According to her bio, mezzo-soprano Victoria Livengood has sung Carmen more than 200 times, and that includes performances at the Met. She has a voice of extraordinary power, beauty, and range… She was in character from the moment she entered to the moment she left the stage, even miming conversation when she wasn’t singing. She played the castanets, struck her tambourine against her knee and butt, did a Gypsy dance, winked at members of the audience, swigged from a wine bottle, even mopped Rink’s neck with her hanky during the “Habanera.” When Carmen throws back at Don José the ring he’d given her, Livengood bit it off her finger and spat it at him! But little seemed spontaneous. After 200 Carmens, she indeed knows what works. Yet her conception was a cliché, the campy vamp rather than the tragic heroine who needs her freedom more than any lover and realizes that someday she’ll die for it. Still, it was certainly a performance.” – Lloyd Schwartz, Boston Phoenix, June 3, 2008

“Over the years, Chorus pro Musica under artistic director Jeffrey Rink has built an extremely loyal and enthusiastic following for its annual performance of opera in concert. Last June's offering took place in a sweltering Jordan Hall, where even a broken ventilation system could not dampen audience spirits. This year, on Sunday afternoon, a capacity crowd packed into the same hall, happily climate-controlled, for a lively and high-octane performance of "Carmen."…In the title role on Sunday was the formidable Victoria Livengood, who has made a specialty of Carmen, having performed it over 200 times according to her bio. Her take on Bizet's cigarette girl was sultry, earthy, defiant, aggressive, entertaining, and totally over the top. She made eyes at individuals in the crowd, swigged wine from an open bottle, swatted Rink's backside with a tambourine while he was conducting, and in the last scene, removed Don José's ring with her teeth and spit it back at his feet. (If Adam Klein's Don José had not been armed with an imaginary knife, I'm not sure who would have won in a duel.) Vocally, Livengood's presence was just as large, with a mezzo-soprano of Wagnerian heft, a solid top, and husky lower range. Indeed, beneath all the campy overacting were the ingredients of an unusual and compelling Carmen that never fully gelled. Klein seemed to throw everything he had into creating a Don José that could keep up with this Carmen,…this was a deeply committed performance that conveyed the desperation of a man coming slowly yet completely unglued. Nouné Karapetian sang a sensitive Micaëla with a light and sweet soprano, and she also stood out for the way she scaled her voice appropriately to the intimate dimensions of Jordan Hall. Baritone Robert Honeysucker sang…a{n} elegant Escamillo, and the smaller roles were ably filled out by Brian Major, Benjamin Werth, Sarah Beckham, Sara Bielanski, John Gomez, and Gregg Jacobson. The chorus was prepared for this program by Louis G. Burkot, and its sound was abundant, forceful, and attractive in tone... Under Rink's baton, the orchestral playing on Sunday…had the requisite heat and finesse when it counted. Julia Scolnik (flute) and Martha Moor (harp) cast the right spell in the big solo before Act III, and other notable contributions came from Andrea Bonsignore (oboe), Steven Jackson (clarinet), and Donald Bravo (bassoon). The New England Conservatory Children's Chorus did itself proud.” Jeremy Eichler, The Boston Globe, June 4, 2008

Carmen: Tragedy at the Comique

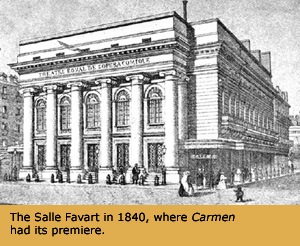

George Bizet’s Carmen first stormed onto the stage of Paris’s Opéra-Comique in 1875. At that time, the city’s major opera company, the Opéra, had just moved into the sumptuous Palais Garnier as part of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s master plan for the rebuilding of Paris, which included the construction of monumental buildings and grand boulevards. This new opera house, now one of the most famous Parisian landmarks, was a crowning achievement of the imperial redesign of Paris. The Opéra had inhabited eight theaters since its founding in the 1700s and had recently been rendered homeless once again when the opera house on the rue Lepelletier burned in 1873. Meanwhile, the Opéra-Comique, which originated in performances held at various fairs in Paris, had by the early 1800s also become a major opera company. Its home was the Salle Favart, an opera house located in the Place Boieldieu a few blocks from the Palais Garnier. This theater was built in 1840, replacing an earlier house that burned in 1838, and it stood until it too was destroyed by fire in 1887.

George Bizet’s Carmen first stormed onto the stage of Paris’s Opéra-Comique in 1875. At that time, the city’s major opera company, the Opéra, had just moved into the sumptuous Palais Garnier as part of Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s master plan for the rebuilding of Paris, which included the construction of monumental buildings and grand boulevards. This new opera house, now one of the most famous Parisian landmarks, was a crowning achievement of the imperial redesign of Paris. The Opéra had inhabited eight theaters since its founding in the 1700s and had recently been rendered homeless once again when the opera house on the rue Lepelletier burned in 1873. Meanwhile, the Opéra-Comique, which originated in performances held at various fairs in Paris, had by the early 1800s also become a major opera company. Its home was the Salle Favart, an opera house located in the Place Boieldieu a few blocks from the Palais Garnier. This theater was built in 1840, replacing an earlier house that burned in 1838, and it stood until it too was destroyed by fire in 1887.

The Opéra-Comique catered to a different audience than the Paris Opéra. The very opulence of the Palais Garnier was indicative of one of the differences between its audience and that of the Comique: the Opéra was for the upper class, the Comique for the middle class. The Opéra presented grand, lengthy, and tragic operas usually in their original language, always in five acts and always with a lavish ballet late in the evening; the Comique offered lighter, more family-oriented works, always performed in French and with spoken dialogue rather than sung recitatives. Its composers included Halévy, Auber, Offenbach, and Berlioz. By the time the Palais Garnier opened, the Comique had been suffering a decline in attendance, both because of the flood of publicity that surrounded the new house and because the core audience of the Comique was now being attracted to theaters offering operettas, which, like the Comique’s repertoire, were works offering family-friendly light fare with spoken dialogue. Even more than the Opéra, the Comique was steeped in tradition, both in terms of the nature of the works performed and in the style of singing it had developed. By the 1870s, its management sought a way to revitalize its reputation and better compete with the grand new theater. Its director, Camille Du Locle, approached Bizet to create an opera in a new genre to inaugurate this new era for the Comique, apparently cognizant of the fact that Bizet had already written works touching on the exotic.Carmen, which had its premiere on 3 March 1875, represented a major change for the Comique in that it ended with the death of one of its protagonists. “Death at the Comique?” was the reaction of one contemporary critic. The production was innovative for the Comique in other respects: the chorus took an active role in the production, rather than standing in line at the back of the stage. They were asked to make entrances and exits and to interact with the principals, which contributed to the realism of the performance. Apparently, the brutality of the story and its treatment made it difficult for audiences and critics accustomed to the classical French style to appreciate the quality of the music and libretto. In addition, Bizet’s use of thematic signatures for some of the characters (as well as a motif representing fate) led to accusations of German influence, which further alienated the conservative Parisian audience.

At the first performance, act 1 was well received and the prelude to act 2 and the Toreador Song earned favorable reactions from the audience; the prelude, in fact, was encored. By the end of act 2, however, audience enthusiasm had noticeably cooled; the audience’s response to the remaining two acts was described as “frigid.” This was mirrored by the press response: it was more the notoriety of the piece than its reported musical merits that attracted audiences to subsequent performances during the initial run. One critic commented: “Carmen presents most unsavory characters, in such bad taste that the work might very well be ill-advised.” Although the opera was performed nearly forty-five times in the year of its premiere, the “squalor and depravity” of the heroine, even as toned down in Bizet’s libretto as compared to its literary source, was too much for Parisian audiences of the day, and the work disappeared from the Parisian repertoire; at the end of the initial run, the director of the Comique resigned. Bizet, prone to illness when under stress, died of a heart attack only three months after the premiere, believing the opera to have been a failure.

Success had to wait for performances outside of the Salle Favart. Three years after Bizet’s death, the London performance of 22 June 1878 at His Majesty’s Theatre, starring the American Minnie Hauk, marked a major turning point for the work’s reputation and can be considered to be the start of its enduring popularity. Performances outside of France, usually in Italian, met with great acclaim, and by the time of the Paris revival of 1883, the work was considered a masterpiece.

It is believed that Bizet first wrote the part of Carmen with the operetta singer Zulma Bouffar (1843-1909) in mind, but she turned down the role, possibly because she did not want to be “stabbed” on stage. His second choice was Marie Rôze (1846-1926), but after discussing the part with Bizet she felt she would not be suited to the role, although she did sing it in 1878. Celestine Galli-Marié (1840-1905), who had created the title role in Thomas’s Mignon, worked closely with Bizet, reportedly collaborating with him in the composition of the Habañera; she was unhappy with the original text, and reportedly twelve drafts of the verses were rejected before the aria took its final form.

The other principal singers at the premiere were Mlle Chapuy as Micaëla, Paul Llhérie as Don José, and Jacques-Joseph Bouhy as Escamillo, under the baton of Louis Michel Adolphe Deloffre. It was first seen in the United States at the Academy of Music in New York on 23 October 1879. The Metropolitan Opera first mounted the work on 9 January 1884, in a performance that was sung in Italian.

The performance of Carmen presents a series of decisions having to do with the selection of which version to use. The spoken dialogue separating the sung set-pieces proved to be a stumbling block for non-French singers; most early performances outside of France were performed in the local languages, and it was determined that substituting sung recitatives would be necessary to allow performances in French outside of France. Such recitatives were provided by Ernest Guiraud, one of Bizet’s colleagues, for the Vienna premiere in October 1875. Most performances today, however, have reverted to the original version with—usually abridged—spoken dialogue.

Carmen is based on a novella by Prosper Mérimée that delved into aspects of the French psyche and philosophy of the time, as well as French attitudes toward gender and class. These include an interest in exoticism and the contrast between the rational French citizen and the untamed, superstitious, and violent creature untouched by French civilization. The vaguely defined gypsies of the novel and, to a lesser extent, the libretto could represent the denizens of any exotic locale. They are mostly created out of the imagination of the author rather than ethnological research. Mérimée had left France for Spain to escape a number of unsuccessful love affairs, at least one of which had involved him in a duel. In one of his short stories based on his experiences in Spain, a waitress named Carmencita, described as a witch and a devil, serves him. The character returned in a slightly different form when Mérimée came to write Carmen about fifteen years later.

Bizet himself had never been to Spain; the Spanish color of the score derives from Bizet’s employment of what audiences of the time expected Spanish music to sound like and from whatever exposure Bizet had to Spanish music heard on the streets of Paris. A popular song by the composer Yradier, possibly based on a traditional folk song from Cuba, served as the basis for the Habañera (the title derives from the city of Havana). It was most likely heard by Bizet when it was performed by the Parisian music hall singer Céleste Venard. Some have suggested that Venard herself may have served as Bizet’s model for Carmen.

Having read Mérimée’s novella, Bizet realized its potential as an opera and sent it to Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy with instructions to turn it into a libretto, with Meilhac contributing the dialogue and Halévy the verses. They turned the original story, which is related by an archaeologist-narrator who had heard the story from the Spanish bandit Don José, into something milder than Mérimée’s original; for example, they eliminated the character of Carmen’s husband, Garcia le Borgne, who was described in the novella as “a villainous monster.” Bizet was able to reinstate some of Carmen’s fierceness in the Habañera, for which he himself supplied the words.

Despite its Spanish setting and occasional use of authentic musical materials, Carmen is a purely French opera. Its vocal demands are those typical of the French repertoire: a forward placement of the voice, a strong use of the so-called head voice, the ability to sing high notes softly, emotions conveyed with a cool elegance rather than an overtly heart-on-sleeve style.

Who is Carmen? Vocally speaking, is she a mezzo-soprano, like such famous Carmens of recent years as Marilyn Horne, Risë Stevens, Grace Bumbry, Tatiana Troyanos, Shirley Verrett, or Agnes Baltsa? Or is she a soprano, like Mary Garden, Victoria de los Angeles, or Rosa Ponselle? Sopranos Maria Callas, Leontyne Price, and Anna Moffo all recorded the role, although they never sang it on stage. The first Carmen, Célestine Galli-Marié, was a light mezzo-soprano. Contraltos such as Ernestine Schumann-Heink, and established Brünnhildes—dramatic sopranos—such as Lilli Lehmann and Martha Mödl have essayed the role. The light coloratura soprano Adelina Patti attempted it, but the performance was not a success (in later years she denied that she ever sang the role).

Who is Carmen? Vocally speaking, is she a mezzo-soprano, like such famous Carmens of recent years as Marilyn Horne, Risë Stevens, Grace Bumbry, Tatiana Troyanos, Shirley Verrett, or Agnes Baltsa? Or is she a soprano, like Mary Garden, Victoria de los Angeles, or Rosa Ponselle? Sopranos Maria Callas, Leontyne Price, and Anna Moffo all recorded the role, although they never sang it on stage. The first Carmen, Célestine Galli-Marié, was a light mezzo-soprano. Contraltos such as Ernestine Schumann-Heink, and established Brünnhildes—dramatic sopranos—such as Lilli Lehmann and Martha Mödl have essayed the role. The light coloratura soprano Adelina Patti attempted it, but the performance was not a success (in later years she denied that she ever sang the role).

Dramatically, is she a femme fatale who destroys the life of an honest, if misguided, soldier? Or is she a woman fighting for her own survival who is cut down by a mother-fixated psychopath? One writer has identified four aspects to Carmen’s character: daughter of the people, a flirt, passionate, and superstitious, and he notes that one’s interpretation of the role depends on the balance struck between these four traits. The text offers justification for a variety of approaches: she is described as a demon and a sorceress, but also as mignonne [sweet], and Zuniga sings that she is “gentille vraiment,” “truly nice.” The wide range of interpretive solutions possible has often led to excesses and strong critical reactions. The critic John Steane has called the role one “in which it is difficult to make little impression.”

Robert Baxter has noted two extreme approaches in his discussion of the Carmens of Maria Gay (1879-1943) and Ninon Vallin (1886-1961): “Gay, a Spanish mezzo with a booming voice, played Carmen as a coarse, vulgar gypsy. Boldly impudent, she shocked critics with ‘her kicking, spitting and nose-blowing.’ Following Mérimée if not Bizet, she chewed an orange and spat out the seeds before singing the Habañera. Vallin, on the other hand, was not interested in being either coarse or common. The elegant French soprano made a cool, intimate, somewhat straight-laced cigarette girl.” Emma Calvé (1858-1942) sang Carmen 61 times at the Metropolitan Opera alone, and for years her name and that of Carmen were inseparable; her voice—we can hear it on numerous recordings she made beginning in 1902—was described as “high-lying and brilliant.”

Robert Baxter has noted two extreme approaches in his discussion of the Carmens of Maria Gay (1879-1943) and Ninon Vallin (1886-1961): “Gay, a Spanish mezzo with a booming voice, played Carmen as a coarse, vulgar gypsy. Boldly impudent, she shocked critics with ‘her kicking, spitting and nose-blowing.’ Following Mérimée if not Bizet, she chewed an orange and spat out the seeds before singing the Habañera. Vallin, on the other hand, was not interested in being either coarse or common. The elegant French soprano made a cool, intimate, somewhat straight-laced cigarette girl.” Emma Calvé (1858-1942) sang Carmen 61 times at the Metropolitan Opera alone, and for years her name and that of Carmen were inseparable; her voice—we can hear it on numerous recordings she made beginning in 1902—was described as “high-lying and brilliant.”  Minnie Hauk, who sang more than 500 performances as Carmen throughout the world beginning in 1877 was the first Carmen in New York (at the Academy of Music) and London (at Her Majesty’s Theatre), both in 1878; as Herman Klein described her performance: “The gypsy appeared strutting forward with hand on hip and flower in mouth. . . . The voice itself was not remarkable for sweetness or sympathetic charm, though strong and full enough in the middle register, but somehow, its rather thin, penetrating timbre sounded just right in a character whose music called for the expression of heartless sensuality, caprice, cruelty and fantastic defiance.” Rosa Ponselle attempted Carmen at the Metropolitan in 1936; she had been coached by former director of the Opéra-Comique Albert Carré and daringly dressed in costumes by Valentina—that for the last act resembled a matador’s outfit, with a blood-red satin cape; the negative response from the critics—calling Ponselle’s approach too “tough”—recalled that of the first Paris performance and was a major factor in Ponselle’s retirement from the operatic stage.

Minnie Hauk, who sang more than 500 performances as Carmen throughout the world beginning in 1877 was the first Carmen in New York (at the Academy of Music) and London (at Her Majesty’s Theatre), both in 1878; as Herman Klein described her performance: “The gypsy appeared strutting forward with hand on hip and flower in mouth. . . . The voice itself was not remarkable for sweetness or sympathetic charm, though strong and full enough in the middle register, but somehow, its rather thin, penetrating timbre sounded just right in a character whose music called for the expression of heartless sensuality, caprice, cruelty and fantastic defiance.” Rosa Ponselle attempted Carmen at the Metropolitan in 1936; she had been coached by former director of the Opéra-Comique Albert Carré and daringly dressed in costumes by Valentina—that for the last act resembled a matador’s outfit, with a blood-red satin cape; the negative response from the critics—calling Ponselle’s approach too “tough”—recalled that of the first Paris performance and was a major factor in Ponselle’s retirement from the operatic stage.  Risë Stevens has described her approach to the role: “[It] must be beautifully and musically sung, with all of the shadings and musical nuances. I interpreted Carmen as a sensuous female, with a powerful seductive quality, with not a spark of honesty, a person who prevails among thieves—a very vital, irresistible woman. . . . I gave her a catlike quality. Carmen must mesmerize those around her, and especially the audience, from her very first entrance.” Perhaps the role’s ability to encompass such a wide range of dramatic and vocal styles accounts in part for its greatness.

Risë Stevens has described her approach to the role: “[It] must be beautifully and musically sung, with all of the shadings and musical nuances. I interpreted Carmen as a sensuous female, with a powerful seductive quality, with not a spark of honesty, a person who prevails among thieves—a very vital, irresistible woman. . . . I gave her a catlike quality. Carmen must mesmerize those around her, and especially the audience, from her very first entrance.” Perhaps the role’s ability to encompass such a wide range of dramatic and vocal styles accounts in part for its greatness.

Don José offers a character nearly as complex as Carmen herself, although the libretto of Carmen leaves out much detail that helps explain Don José’s actions, and the version with the sung recitative loses even more of this background information. Don José’s vocal demands present a challenge for any tenor; few have at their command both the dramatic heft necessary for much of the role and the ability to sing the pianissimo high B flat called for at the end of the ‘Flower Song,” a note that must be sung as written if it is to “suggest a gentle reproach, not a furious accusation,” in the words of John Steane.

The character of Micaëla does not appear in Mérimée, which may explain why she is less well drawn than the other characters; the character was needed to supply a “pure” figure to make the story seem more respectable to an audience accustomed to “family” fare. The addition was fortunate, however, as it provides the lovely act 1 duet with Don José and the exquisite act 3 aria “Je dis, que rien ne m’épouvante.” Both Micaëla and Escamillo are reminiscent of standard characters in the genre of opéra-comique who would have been immediately recognizable by any audience member.

Carmen’s early and lasting popularity is reflected in the fact that several of its arias have been recorded by artists almost since the beginning of the record industry. A lithograph from 1878 (widely distributed on the cover of the sheet music for “The Phonograph March”) shows Marie Rôze, mentioned earlier as one of Bizet’s first choices to create the role of Carmen, recording into a tinfoil phonograph, just one year after Edison’s invention; although it is not known what she was singing into the recording horn (the tinfoil record would have been destroyed in the process of removing it from the machine), she did sing the role (for the Carl Rosa Company) in that same year, and it is tempting to imagine that she was singing the Habañera. As early as 1895, when the phonograph had just become practical for home use, several recordings were issued of the Toreador Song made for Emile Berliner’s Gramophone Company. The first complete Carmen recording was made in 1908, in German, starring Emmy Destinn. An early recorded version exists that takes us back to the original Opéra-Comique version. This recording of Carmen was made by the firm of Pathé-Frères in 1911 with a cast taken entirely from the roster of the Comique; until 1950 it was the only recording to use the spoken dialogue. It is our closest link to the style of singing characteristic of the Comique in Bizet’s time; Ward Marston has recently issued the performance on his CD label.

Carmen’s early and lasting popularity is reflected in the fact that several of its arias have been recorded by artists almost since the beginning of the record industry. A lithograph from 1878 (widely distributed on the cover of the sheet music for “The Phonograph March”) shows Marie Rôze, mentioned earlier as one of Bizet’s first choices to create the role of Carmen, recording into a tinfoil phonograph, just one year after Edison’s invention; although it is not known what she was singing into the recording horn (the tinfoil record would have been destroyed in the process of removing it from the machine), she did sing the role (for the Carl Rosa Company) in that same year, and it is tempting to imagine that she was singing the Habañera. As early as 1895, when the phonograph had just become practical for home use, several recordings were issued of the Toreador Song made for Emile Berliner’s Gramophone Company. The first complete Carmen recording was made in 1908, in German, starring Emmy Destinn. An early recorded version exists that takes us back to the original Opéra-Comique version. This recording of Carmen was made by the firm of Pathé-Frères in 1911 with a cast taken entirely from the roster of the Comique; until 1950 it was the only recording to use the spoken dialogue. It is our closest link to the style of singing characteristic of the Comique in Bizet’s time; Ward Marston has recently issued the performance on his CD label.

According to Susan McClary, more than sixteen filmed versions of the Carmen story had been made by 1948. Geraldine Farrar’s success in the role at the Metropolitan led Cecil B. DeMille to cast her in a silent-film version in 1915. Other films include two versions entitled Gypsy Blood, the first a silent film starring Charles Chaplin and Pola Negri. Otto Preminger created a film version of Oscar Hammerstein’s all-black, Americanized 1943-44 Broadway musical Carmen Jones in 1954, with Marilyn Horne supplying the singing voice for Dorothy Dandridge. Carlos Saura released a flamenco Carmen in 1983; and Francesco Rosi’s 1984 treatment starred Julia Migenes-Johnson and Placido Domingo. The success of many of these treatments attests to the resilience of the character of Carmen and of the work.

By the 1980s, Carmen was the third most frequently performed opera at the Metropolitan, following Aida and La Bohème. Ironically, the opera that brought tragedy to the Comique and was an apparent failure at its first performance has become the most popular opera ever premiered at that theater and one of the most enduring masterpieces in the operatic repertoire.

—Michael Sims

Other information:

The mission of Concert Opera Boston is to sponsor outstanding and affordable performances of concert opera in the greater Boston area. Concert Opera Boston also supports educational activities and other initiatives that enhance the appreciation of opera.