Concert Performance

Sunday, May 31, 2009 at 3PM

New England Conservatory's Jordan Hall, Boston

Puccini’s Turandot

conducted by Jeffrey Rink

“No one shall sleep!” “Nessun dorma!”

Concert Opera Boston was proud to be the major sponsor of Chorus pro Musica's outstanding sold out concert opera performance on Sunday, May 31, 2009 of Puccini’s final opera, Turandot. Left unfinished at his death (and completed by his student Franco Alfano), Turandot is based on Carlo Gozzi’s fairy-tale drama about an icy Chinese princess and the prince who dares try to solve her three riddles. If he fails, he will die. Premiered on April 25, 1926, Turandot includes the famous arias “In questa reggia” and “Nessun dorma.” Maestro Jeffrey Rink was joined by a superb cast including Othalie Graham as Turandot, Kip Wilborn as Calaf, Eleni Calenos as Liu, Todd Robinson as Timur, David Kravitz as Ping, Frank Kelly as Pang, Charles Blandy as Pong, Benjamin Werth in the role of the Mandarin and Richard Conrad as the Emperor, Chorus pro Musica and orchestra. The performance was sung in Italian with translations projected in English. Michael Sims, author of Concert Opera Boston’s notes on Turandot and previous operas, gave a pre-concert lecture. Chorus pro Musica dedicated the performance of Turandot to the memory of Fi Saad, one of the founders of Concert Opera Boston.

The critics praised the performance:

“Chorus pro Musica's former director Jeffrey Rink returned to conduct the group on Sunday; its 60th-anniversary season closed with concert opera, an annual tradition Rink started in the 1990s. … Puccini's swan song is an opera to be happily overwhelmed by, and the group delivered in formidable fashion. ‘Turandot’ also ranks as a choral showpiece; especially in its first act, with the titular princess at a distance but her murderous regard for unworthy suitors front-and-center, the crowd carries huge stretches of the drama. The chorus…dove in with brio, rhythmically grounded, textually clear, ranging in color from spectral hush to quintessential grand-opera peroration. (A contingent of children from the Boston City Singers lent tonal innocence from the balcony.) Puccini's protagonists verge on forces of nature; both respective soloists embraced that larger-than-life aspect. Kip Wilborn, making his Boston debut, sang Calaf with unremitting bravado, braving Turandot's riddles as much for competitive thrill as amorous reward. His full-bore attack left the edges of his voice slightly frayed by the time Act III's "Nessun dorma" came around, but Calaf's steamroller confidence was entertainingly palpable. Turandot has a notoriously tough entrance, launching into the aria ‘In questa reggia,’ and Othalie Graham's immense voice took time to warm up. But the Canadian soprano's timbre and power were thrilling - steely ring from top to bottom - and her path from imperiousness to passion was convincing. Todd Robinson's generously tolling bass gave Timur a stoic gravity. As Liu, Eleni Calanos, a recent graduate of Boston University's Opera Institute, sang with an arresting, dark warmth... Benjamin Werth, another BU student, brought impressive presence to the Mandarin's brief, expository role…Ping, Pang, and Pong, the princess's put-upon bureaucrats, found ideal realization in local stalwarts David Kravitz, Frank Kelley, and Charles Blandy. The trio's comic precision and matched musical flair made one wish they had the playground of a full staging. And Boston institution Richard Conrad sang the role of the old Emperor, often a sinecure for aged legends; Conrad belied that pattern with elegant lyricism and a flawless legato, a connoisseur's delight…Rink is an unobtrusive conductor, but superbly attuned to singers' breathing and phrasing, and the polish and vividness of the pick-up orchestra was witness to his effective artistry. With noble pace, the prodigious sonic bloom engulfed the room. As it should: No matter the vessel, ‘Turandot’ overflows.” — Matthew Guerrieri, The Boston Globe, June 3, 2009

“Last Sunday at Jordan Hall, Boston’s Chorus Pro Musica wrapped up its 2008-09 season, while Jeffrey Rink concluded his tenure as the group’s music director. Appropriately, Puccini’s final opera, Turandot, was the work presented, and it received a spectacular reading by the chorus, in peak form, an excellent orchestra, and a superlative group of singing actors. Chorus Pro Musica has often programmed operas in concert version, but, in honor of the group’s 60th anniversary, and Rink’s departure, the chorus sang its collective heart out on Sunday. And Turandot afforded them ample opportunity. In addition to abundant, brilliant choral writing, Turandot features lush orchestral sonorities, tinged with Asian colorings, and some of Puccini’s most glorious arias... Puccini’s last opera marks his return to unabashed lyricism, and arias like Nessun Dorma are now among his most popular. Turandot is also the grandest of Puccini’s work, one in which he leaves behind the simpler human melodramas of his Verismo operas, like La Boheme and Madama Butterfly. The tale of an icy Chinese princess whose heart is warmed by a fearless stranger is set on a magnificent scale. With the exception of Liu, the principal characters are virtually symbolic, larger than life figures. And certainly, the roles require major voices to do them justice. Despite its ancient Chinese locale, Turandot is a true Italian opera, and, therefore, the primary focus is on the solo singing. The cast assembled for Sunday’s performance was uniformly first-rate, one that would not fail to impress in any of the world’s major opera houses. Though performed in concert version, the opera was semi-staged, with the singers acting out their parts at the front of the stage before the orchestra and chorus. The title role was sung by Othalie Graham, a remarkable Canadian soprano who has made something of a specialty of the grueling role, and has apparently survived unscathed. Her voice is sumptuous, with firmly-focused, penetrating high notes that subjugated the other onstage performing forces. Those awesome high C’s were made even more impressive by her dead-on intonation. Possessing beauty, temperament and superb acting skills, Graham is destined for stardom in the world of opera. The Met would do well to snag her for their roster. As the heroic Calaf, who nearly loses his head over the mysterious princess, tenor Kip Wilborn was excellent. Like that of Graham’s, Wilborn’s full-throated sound was scaled for a venue much larger than Jordan Hall. With its baritone color, his voice was secure in the low register, though occasionally inconsistent in the middle. However, his thrilling high notes more than compensated, and rang through the hall with trumpet-like clarity. His Nessun Dorma was nicely realized and very well received. A graduate of the BU Opera Institute, Eleni Calenos performed the role of Liu, the unfortunate slave who sacrifices her life for her beloved Calaf. Waif-like in stature, Calenos nonetheless produced an impressive sound, proving, along with great recorded Lius like Tebaldi, Caballe and Scotto, that the part is well-suited to a larger voice. The only element lacking in her fine singing was a true, high pianissimo, which is de rigueur for this role. Yet Calenos phrased sensitively, and was an ingratiating stage presence. Transforming from a Czech peasant in BLO’s recent Bartered Bride to Ping, the Grand Chancellor of China, baritone David Kravitz chalked up another fine characterization to his growing list of accomplishments. A fine comedian and solid singer, he is always enjoyable to hear and watch. With respect to repertoire, he cannot vie with the astounding Frank Kelley, who added the role of Ping to his voluminous resume. Along with Charles Blandy as Pong, he added surefire comic relief to this solemn fable. Todd Robinson’s warm basso was nicely suited to the part of Calaf’s father, Timur. He was quite moving in his Act III farewell to Liu. A veteran of the Boston operatic stage, Richard Conrad appeared in the small role of Turandot’s father, the supreme ruler of China. Having warmed up vocally, he created a wonderfully regal emperor. The contributions of the chorus and orchestra cannot be overstated. Jeffrey Rink was in firm control of his legion of performers, down to cueing the delightful children’s chorus that was nestled in the balcony. He conducted with total authority. His tempi were, for the most part, fleet; though he provided a spacious framework for Liu’s lyric arias. The opera’s rousing finale drove the appreciative audience to its feet, and left us hoping to see Rink someday return to Chorus Pro Musica in the role of guest conductor.” — Ed Tapper, EDGE, June 2, 2009

Turandot: A Tradition Ends

From its origins in the sixteenth century through its two great peaks, the flowering of the bel canto period in the 1830s and the rise of the naturalistic verismo school in the 1890s, Italian opera maintained its status as the world’s leading source of lyric drama. By the time of the first performance of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot in 1926, however, the wellspring of Italian opera had all but run dry. Turandot is the last Italian opera to secure a place in the standard repertoire.

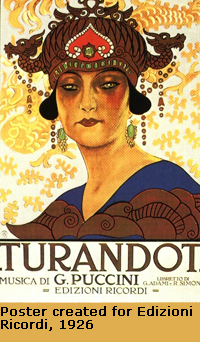

Puccini (1858–1924) was not an especially prolific opera composer, having published only twelve operas (if we count the three works of Il trittico separately). Part of this stemmed from his difficulty in finding sources for librettos that satisfied him. After the premiere of Il trittico at the Metropolitan Opera in 1918, Puccini began a search for a suitable play on which to base his next opera. After considering and rejecting a long list of sources, his chosen librettists, Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, suggested that he write an opera based on Carlo Gozzi’s 1761 play Turandotte. Adami had already provided Puccini with two librettos, for La rondine (1917) and Il tabarro (1918). Simoni was the author of a stage work about Gozzi, who was a champion of the tradition of the commedia dell’arte, or comedy of masks, with its stock characters familiar to all Italians. Turandotte, based on a traditional folktale, was Gozzi’s most significant effort in the revival of this tradition, and it had already served as the source of a large number of other musical works, including Weber’s incidental music to Friedrich Schiller’s 1802 treatment of Turandotte, Puccini’s teacher Antonio Bassi’s 1867 opera Turanda, and Ferruccio Busoni’s whimsical fairy-tale opera Turandot (1917). Simoni gave Puccini an Italian translation of the Schiller version, and Puccini was sufficiently intrigued to embark on the creation of what was to be his last opera.

Turandotte, based on a traditional folktale, was Gozzi’s most significant effort in the revival of this tradition, and it had already served as the source of a large number of other musical works, including Weber’s incidental music to Friedrich Schiller’s 1802 treatment of Turandotte, Puccini’s teacher Antonio Bassi’s 1867 opera Turanda, and Ferruccio Busoni’s whimsical fairy-tale opera Turandot (1917). Simoni gave Puccini an Italian translation of the Schiller version, and Puccini was sufficiently intrigued to embark on the creation of what was to be his last opera.

Although Puccini was the most successful of the verismo composers, by the time of Turandot the verismo style was all but dead. Turandot is not a veristic work, involving as it does princes and a princess in a nonrealistic, fable-like setting. It does not concern what Puccini called the piccole cose (“small things,” the everyday matters) of verismo. The work represents Puccini’s only foray into the realm of myth (although his first opera, Le villi, involves some supernatural elements). It does, however, contain much music instantly recognizable as Puccini, it features at least one typical Puccinian character, and it contains the emotionally direct music that characterized his earlier works. But Turandot stands apart from Puccini’s other operas in its scale, its timelessness, and its remoteness.

The icy, man-hating Princess Turandot, daughter of the Emperor Altoum, has sworn vengeance against all men; she has taken a sacred oath that she will marry only a man of noble birth who can solve her three riddles; the penalty for failure is death. When the opera begins, Turandot’s twenty-seventh victim, the Prince of Persia, is being led to his execution. The role of Turandot calls for a dramatic soprano, and Puccini builds a sense of anticipation by having her not sing until act 2, scene 2.

Timur, the deposed king of Tatary, who is portrayed as blind in most productions, is sung by a bass. He is accompanied by the slave-girl Liù (lyric soprano). Liù is in love with Timur’s son Calaf (tenor); she fell in love with him when, one day at the palace, he smiled at her, and on the basis of that tiny gesture she has devoted her life to serving Calaf’s father. Calaf is living incognito in Peking as a fugitive. Turandot’s three ministers, the Grand Chancellor Ping (baritone), the General Purveyor Pang (tenor), and the Chief Cook Pong (tenor)—a connection to the “masks” of the commedia dell’arte—are cynical and slightly sinister characters who nevertheless reveal a strain of nostalgia for the country life in the midst of Turandot’s reign of terror and show a sympathetic side at the death of Liù.

A question that has followed Turandot around for decades concerns the proper pronunciation of the title character’s name. The name Turandot apparently is derived from the Persian “Turandokht,” meaning “daughter of Turan,” Turan being a region of what was then Persia, later called Turkestan. The name Turandokht and the fact that Gozzi’s play was entitled Turandotte imply that the final t should be pronounced. However, according to Rosa Raisa, who created the title role, Puccini pronounced it without the final t.

Turandot represents a summing-up of the grand tradition in its combination of structural and harmonic conventions of Italian opera. The work, although “through-composed,” that is, running continuously without breaks within its scenes, contains the standard elements characteristic of a “number” opera—arias, duets, choruses, dialogues, interludes, and climactic ensembles.

Puccini biographer Mosco Carner has identified four genres characteristic of Puccini’s style, all of which occur in Turandot: the lyric-sentimental, represented here by Liù; the heroic-grandiose, represented by Calaf and Turandot; the comic-grotesque, represented by the three ministers; and the exotic or “oriental.” This “orientalism” in Turandot is of a rather vague, pan-Asian character. Although the title character is identified as Chinese (and the slave girl Liù and the three ministers have Chinese-derived names), many of the other characters in the opera are Middle Eastern; in addition to the Tatars Calaf and Timur, there is also Turandot’s first victim in the opera, the Prince of Persia. William Ashbrook and Harold Powers similarly describe four tinte, or colorations, in Turandot; these are Chinese (pentatonic, corresponding to the black notes on the piano), Middle Eastern, Romantic-Diatonic (the traditional European harmonic tradition), and Dissonant (including use of the tritone, the so-called “devil’s interval,” heard most notably in the portrayal of the ghosts of Turandot’s victims). Thus two European musical traditions—the lush harmonies and orchestration of the late romantic style and the dissonance and polytonality of Stravinsky—are combined with two “exotic” traditions, creating the most sophisticated palette of any Puccini opera.

Puccini drew on several threads in creating his opera. In addition to the commedia dell’arte figures of Ping, Pang, and Pong, in the character of the slave girl Liù he has a typical Puccinian “little woman,” in the tradition of Mimi in La bohème. The scoring is on the scale of grand opera, and the opera features a far larger role for the chorus than in any of his other works. In addition to its dependence on the pentatonic scale, it draws on four authentic Chinese melodies included in the 1884 book Chinese Music by van Aalst as well as three tunes Puccini heard played on a music box owned by his friend and former Chinese consul Baron Fassini. (These are “Mo-li-hua,” or “Jasmine Flower,” heard first in the Children’s Chorus “Là, su i monti del l’est” and numerous other times throughout the opera; the so-called “Imperial Hymn,” which appears at “Diecimila anni al nostro Imperatore,” when the ancient Emperor Altoum appears on his ivory throne; and the music that accompanies the entrance of the three ministers—“Ferma! che fai?”). It also derived from what Ashbrook and Powers refer to as “Puccini’s natural pentatonic penchant,” heard most notably in Madama Butterfly, but also hinted at in works as early as Manon Lescaut. In keeping with the pan-Asian elements in the story, other “exotic” musical elements are present as well, including what has been described as a “Middle-Eastern orientalism” featuring pedal drones and particular percussion effects. This appears in three sections: the chorus of Turandot’s handmaidens, the Prince of Persia’s cortège, and the ministers’ offer of dancing girls to bribe Calaf into revealing his name. Stravinskian rhythms depict the barbaric, chaotic nature of Turandot’s reign of terror.

The story draws on a number of themes underlying myth, including the initiation rite, the seeking of wisdom and awareness, the male-female dichotomy, and the all-conquering power of love. Although Calaf is appalled by Turandot’s inhumanity, he is powerless to resist her, and he is obsessed with the task of transforming her hatred of men into love for him. Puccini and his librettists added an explanation for Turandot’s hatred of men, which does not exist in the Gozzi play: her ancestor, Princess Lou-Ling, had been raped and killed during a Tatar invasion; by extension she is seeking to avenge the historical subjugation of women by men throughout history. Unlike typical mythical battles that require the victor to demonstrate superior physical prowess, Turandot’s challenge is one of the mind, a battle of wits.

Puccini began working on Turandot in March 1920, with the first music being composed by January 1921. By March 1924 he had completed the music for everything except the final scene. He was unsatisfied with the text of the final duet, which he considered to be the most important part of the opera; he needed a scene strong enough to provide a contrasting balance with the dramatic peak of the act 2 confrontation—Calaf’s solving of the three riddles. Puccini wrote: “It must be a great duet. These two almost superhuman beings descend through love to the level of mankind, and this love must at the end take possession of the whole stage in a great orchestral peroration.” But the librettists, by intensifying Turandot’s cruelty in comparison with the character in the Gozzi play and by introducing the sympathetic character of Liù (not in the Gozzi play), whose death Turandot causes, had made Turandot’s transformation into a loving and sympathetic character all the more challenging.

A heavy smoker throughout his life, Puccini apparently took little notice of a persistent sore throat, but by the beginning of 1924 he began mentioning it in correspondence, and he clearly realized that it was the symptom of something serious. Just two days after deciding on the text for the final duet, he was diagnosed with a malignant, and inoperable, growth on his epiglottis. Although Puccini’s son Tonio was informed of the gravity of his father’s illness, Puccini himself was never told. On November 24, 1924, he began receiving treatment at a radiology clinic in Brussels, which consisted of radioactive needles being inserted into his throat. Although the treatment seemed to be effective at first, it apparently strained his heart, and he died of heart failure on November 29.

Although Puccini’s death was the ostensible cause of his inability to complete the opera, Puccini’s correspondence shows that he felt that justifying a happy ending despite Liù’s suicide was possibly an unsolvable problem. His requests for revision after revision to the text may reflect both his fear that he could not find the right music for the final catharsis and his inability to gather up the strength he needed. Puccini’s sympathies clearly lay with Liù, and her powerful and moving death scene was a stumbling block for the composer; he needed to devise a way to shift the audience’s sympathies from Liù back to Calaf and the newly humanized Turandot, who, after all, is responsible for Liù taking her own life. He struggled with how best to achieve this transformation and avoid having the final scene seem an anticlimax. He needed to convey how Turandot recognizes that Liù’s protection of Calaf’s identity through her suicide was motivated by love, and how Calaf’s kiss—her first—produces an immediate and total capitulation. The librettists, unaware that Puccini’s time was running short, gave priority to other commitments, and the composer’s growing weakness made it impossible for him to compose the crucial final duet. Puccini wrote that he was searching for “the characteristic, lovely, unusual melody” to convey the humanization of Turandot, but it was not to be found. It was not until October 8 that Puccini finally settled on a version of the duet text, and he never progressed beyond thirty-six pages of rough sketches for the finale.

After Puccini’s death, Puccini’s publisher, Casa Ricordi, searched for a composer to prepare a performing version of Puccini’s sketches for the final scene. Pietro Mascagni, Francesco Zandonai, and Vincenzo Tommasini (who had completed Boito’s Nerone after the composer’s death) were considered, but Ricordi decided on Franco Alfano, whose opera La leggenda di Sakùntala resembled Turandot in its setting and heavy orchestration. Alfano’s first version contained much music not derived from Puccini’s sketches and included some additional lines of text that he composed himself;  Ricordi objected (as did its designated conductor, Arturo Toscanini), and Alfano substituted a new version, based more closely on Puccini’s sketches but omitting those passages where Puccini had not left adequate indication of how he wanted the passages to sound. Toscanini cut about six minutes of additional music from Alfano’s ending, reducing it from 375 to 266 bars, and it is this shortened version that is usually performed (the original version was not performed until November 3, 1982, at the Barbican, London, fifty-six years after its composition). In recent years, other attempts to write conclusions to the opera have been made by Janet Macguire, Steven Mercurio, and Luciano Berio.

Ricordi objected (as did its designated conductor, Arturo Toscanini), and Alfano substituted a new version, based more closely on Puccini’s sketches but omitting those passages where Puccini had not left adequate indication of how he wanted the passages to sound. Toscanini cut about six minutes of additional music from Alfano’s ending, reducing it from 375 to 266 bars, and it is this shortened version that is usually performed (the original version was not performed until November 3, 1982, at the Barbican, London, fifty-six years after its composition). In recent years, other attempts to write conclusions to the opera have been made by Janet Macguire, Steven Mercurio, and Luciano Berio.

Alfano attempted to make the final scene sound like Puccini, and his achievement is impressive in many ways. The aria “Dal primo pianto” helps to explain Turandot’s conversion (oddly, many performances cut this aria). Although we will never know exactly how Puccini would have chosen to end his opera, Alfano’s decision to use one of the big melodies from Calaf’s “Nessun dorma” for the final chorus creates a thoroughly Puccinian and theatrically effective, even thrilling, conclusion.

After the disastrous premiere of Madama Butterfly at La Scala, Milan, in 1904, Puccini vowed never to allow any of his operas to have its prima assoluta at that theater. His last two works before Turandot, La fanciulla del West and Il trittico, both had their world premieres at the Metropolitan Opera.  But in the 1922/23 season, La Scala mounted a gala thirtieth anniversary production of Manon Lescaut, Puccini’s first successful opera, and his ire at the theater management, the Milanese press, and its audience finally subsided. Puccini’s high opinion of Toscanini, and the prestige of a premiere at La Scala under his baton, made him determined to have Turandot’s premiere there.

But in the 1922/23 season, La Scala mounted a gala thirtieth anniversary production of Manon Lescaut, Puccini’s first successful opera, and his ire at the theater management, the Milanese press, and its audience finally subsided. Puccini’s high opinion of Toscanini, and the prestige of a premiere at La Scala under his baton, made him determined to have Turandot’s premiere there.

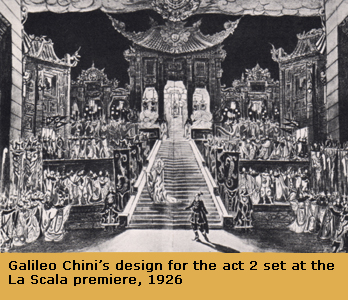

The premiere of Turandot took place at La Scala on April 25, 1926, with Rosa Raisa as Turandot, Miguel Fleta as Calaf, Maria Zamboni as Liù, Giacomo Rimini as Ping, Emilio Venturini as Pang, Giuseppe Nessi as Pong, and Carlo Walter as Timur. (None of these singers were ones Puccini had in mind; he had suggested Maria Jeritza as Turandot, Gilda Dalla Rizza as Liù, and either Beniamino Gigli or Giacomo Lauri-Volpi as Calaf. All but Dalla Rizza were under contract to the Metropolitan Opera, however, and because its general manager Giulio Gatti-Casazza and Toscanini were estranged at the time, Gatti-Casazza threatened to cancel the contract of anyone who participated in any performance conducted by Toscanini.) Apparently at the request of Ricordi, that one performance ended with the last portion composed by Puccini. According to Eugenio Gara, in the middle of act 3, two measures after the words “Liù, poesia!,” Toscanini stopped and laid down his baton. He turned to the audience and announced: “Qui finisce l'opera, perchè a questo punto il Maestro è morto” (“Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died”). The second and subsequent performances, which were conducted by Ettore Panizza, continued with Alfano’s ending, and apparently Toscanini never again conducted Turandot.

In its first year, performances of Turandot spread quickly throughout Europe and as far away as South America. It reached the Teatro Costanzi in Rome four days after the La Scala premiere, with Bianca Scacciati and Francesco Merli (Calaf in the first complete recording) in the leads. It traveled to the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires on June 23 (with Claudia Muzio, Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, and Rosetta Pampanini) and to La Fenice in Venice on September 9. In German translation, it was first seen in Dresden on September 6, 1926 (with Anna Roselle in the title role) followed by Vienna on October 14 (starring Lotte Lehmann and Leo Slezak) and Berlin on November 8. Its United States premiere, at the Metropolitan Opera, was on November 16, with Maria Jeritza, Lauri-Volpi, Martha Attwood, and Giuseppe de Luca under Tullio Serafin. A French-language version was performed at La Monnaie in Brussels on December 17. On January 17, 1927, it was seen at the San Carlo in Naples, followed by Parma on February 12, Turin on March 17, and Bologna in October of that year. Its U.K. première, at Covent Garden, was on June 7, 1927. Anna Roselle sang the role at the San Francisco Opera première on September 19, 1927, a performance that also starred Armand Tokatyan and Ezio Pinza. Paris first saw Turandot on March 29, 1928. It was not performed at the Bolshoi in Moscow until 1931. The Metropolitan Opera unveiled a spectacular new production by Franco Zeffirelli in 1987.

The earliest Boston staging I have been able to trace is the Metropolitan Opera tour performance of April 19, 1961, with Birgit Nilsson, Franco Corelli, and Lucine Amara under the baton of Leopold Stokowski. Sarah Caldwell’s Opera Company of Boston mounted productions in 1983 (Eva Marton, James McCracken, and Sarah Reese) and 1986 (Marton, Janos Nagy, and Reese). Boston Concert Opera’s 1985 concert performance featured Linda Kelm, Colenton Freeman, and Cynthia Haymon, David Stockton conducting, and Chorus pro Musica’s previous Turandot, in 1998, starred Catherine Kelly, Maxwell Lee, and Maria Ferrante under the baton of Jeffrey Rink.

By 1924, when Turandot’s premiere took place, complete recordings of operas were relatively common, and electrical recording had made the capture of full orchestras far more feasible than the earlier acoustic method. For various reasons, however, very few recordings from the opera appeared in the years following the premiere, and none of the music from the opera by its two principals, Rosa Raisa and Miguel Fleta. In 1926, the original Liù, Maria Zamboni, recorded Liù’s two arias, and the original Pang and Pong, Emilio Venturini and Giuseppe Nessi, were joined by the original Mandarin, Aristide Baracchi, as Ping to record two of the ministers’ scenes. (Thirty-one years later, Nessi recorded the role of the old emperor in Maria Callas’s complete recording of the opera.) An effort had been made to preserve the first complete performance on disc (that is, the version conducted by Panizza including Alfano’s finale), but technical problems and the subsequent destruction of the most of the original masters prevented its issue; only two choral scenes from that performance were ever made available. Eva Turner recorded two performances of “In questa reggia” and “O principe” in quick succession in 1928. Other records from Turandot during the 78 era included “Nessun dorma” by Richard Tauber, Antonio Cortis, Beniamino Gigli, Alfred Piccaver, and, perhaps most notably, Jussi Björling. “In questa reggia” received a highly regarded recording by Maria Nemeth; that by the young Lotte Lehmann anticlimactically ends before the final measures. Liù’s arias were recorded by, among others, Lotte Schöne, Eide Norena, and Rosetta Pampanini. In 1937, portions of live Covent Garden performances with Eva Turner, Giovanni Martinelli, and, alternating as Liù, Licia Albanese and Mafalda Favero, all under the baton of John Barbirolli, were recorded; these overlapping excerpts are available on an EMI CD. Also in 1937 the first complete recording of the opera was issued, with Gina Cigna as Turandot, Francesco Merli as Calaf, and Magda Olivero as Liù under Franco Ghione. The next major recording came twenty years later, with Maria Callas, Eugenio Fernandi, and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf under Tullio Serafin. Two recordings feature the Turandot of Birgit Nilsson: one from 1960 with Jussi Björling and Renata Tebaldi under Erich Leinsdorf and one from 1965 with Franco Corelli and Renata Scotto under Francesco Molinari-Pradellii. Perhaps the most successful version yet recorded is that from 1973 conducted by Zubin Mehta, with a surprisingly cast Joan Sutherland as Turandot, Luciano Pavarotti as Calaf, and Montserrat Caballé as Liù. Although all of the commercial recordings use the shortened version of Alfano’s ending, recordings exist of the final scene as Alfano originally conceived it; one such recording is by Josephine Barstow, with John Mauceri conducting, available on a Decca CD.

Before the extensive cuts insisted on by Toscanini were made to Alfano’s original version, Ricordi had commissioned German translations of the work, with the result that a number of scores were printed in Germany containing the complete final scene. Although it is not certain whether Alfano’s original version received any performances at the time, two early German recordings of “Del primo pianto,” Turandot’s aria after Calaf kisses her, give evidence that it had. These recordings, by Anna Roselle and Lotte Lehmann, contain music that exists only in Alfano’s uncut original, implying that it was this version of the score that they had performed on stage.

In the decades following Turandot’s premiere, a number of operas have come out of Italy, notably ones by Respighi, Pizzetti, Malipiero, and Dallapiccola; two operas, Pinotta and Nerone, came from the formerly prolific Mascagni, and Alfano himself produced Cyrano de Bergerac. But not one has become a staple of the standard repertoire. With Turandot, the unbroken, three-hundred-and-fifty-year-old line of Italian opera, led most notably by Monteverdi, Bellini, Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi, Mascagni, Leoncavallo, and Puccini, had come to an end.

—Michael Sims

Other information:

The mission of Concert Opera Boston is to sponsor outstanding and affordable performances of concert opera in the greater Boston area. Concert Opera Boston also supports educational activities and other initiatives that enhance the appreciation of opera.